04

Is it cheating if your company takes credit for an emissions reduction that another company accounts for in their own inventory?

Not necessarily. There is a legitimate opportunity for multiple companies to count the same reduction or removal in their scope 3 if it’s managed the right way.

For some emissions, such as scope 3, double counting is almost impossible to avoid because another company will inevitably count those emissions as their scope 1 emissions.

This also happens in the world of finance, where transactions can be counted more than once. For example, the cost of intermediate goods used to produce a finished product is included in both a company’s reporting and in a nation’s gross domestic product calculation.

That said, some types of double counting can put your reputation at risk by undermining the environmental integrity and credibility of your company’s activities and reporting. In this chapter, we’ll delve deeper into the topic of double counting, paying close attention to when double counting is acceptable and when it’s not. While several examples of double counting will be covered, they don’t represent the entire spectrum of possibilities.

Read all recommendations

Double counting is a normal part of scope 3 emissions accounting. Whether it is problematic depends on how the reported information is used. Here, we’ll look at the key differences between shared accountability (acceptable double counting, also sometimes referred to as co-claiming) and unacceptable double counting.

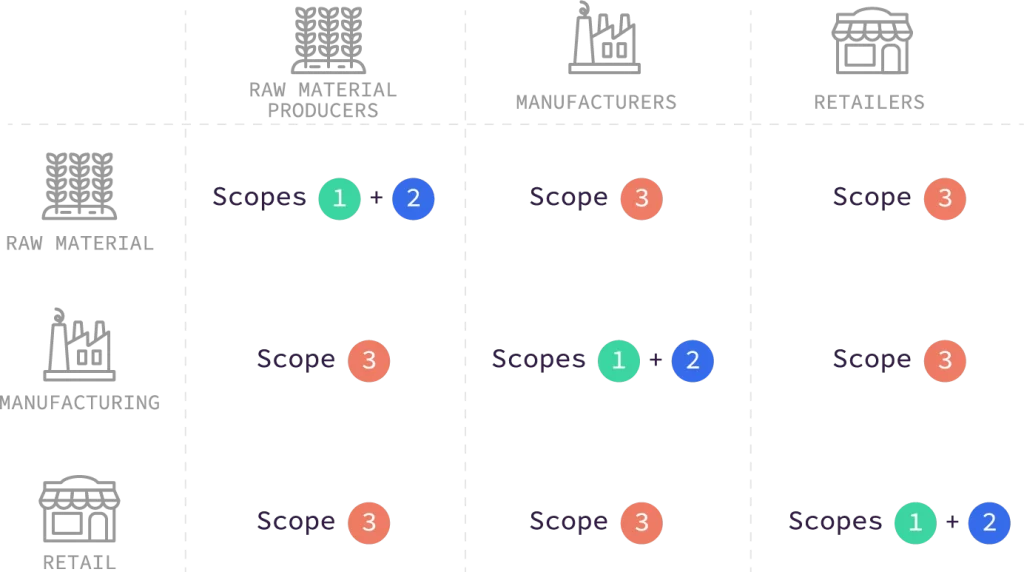

While companies all along the same value chain can account for the emissions associated with their activities, only one is permitted to count them as their scope 1 emissions. There are, however, no limitations on how many companies can count these emissions in their scope 3.

For example, a retailer would account for emissions at its store as scope 1 and 2 and then everything else (extracting raw materials, transforming the raw materials into a finished product, etc.) would count as scope 3. These same scope 3 emissions would be scope 1 and 2 emissions for the raw materials producers or product manufacturers in the retailer’s value chain.

Rigorously following standards and being clear about what is counted for in each scope is vital to provide clarity to stakeholders.

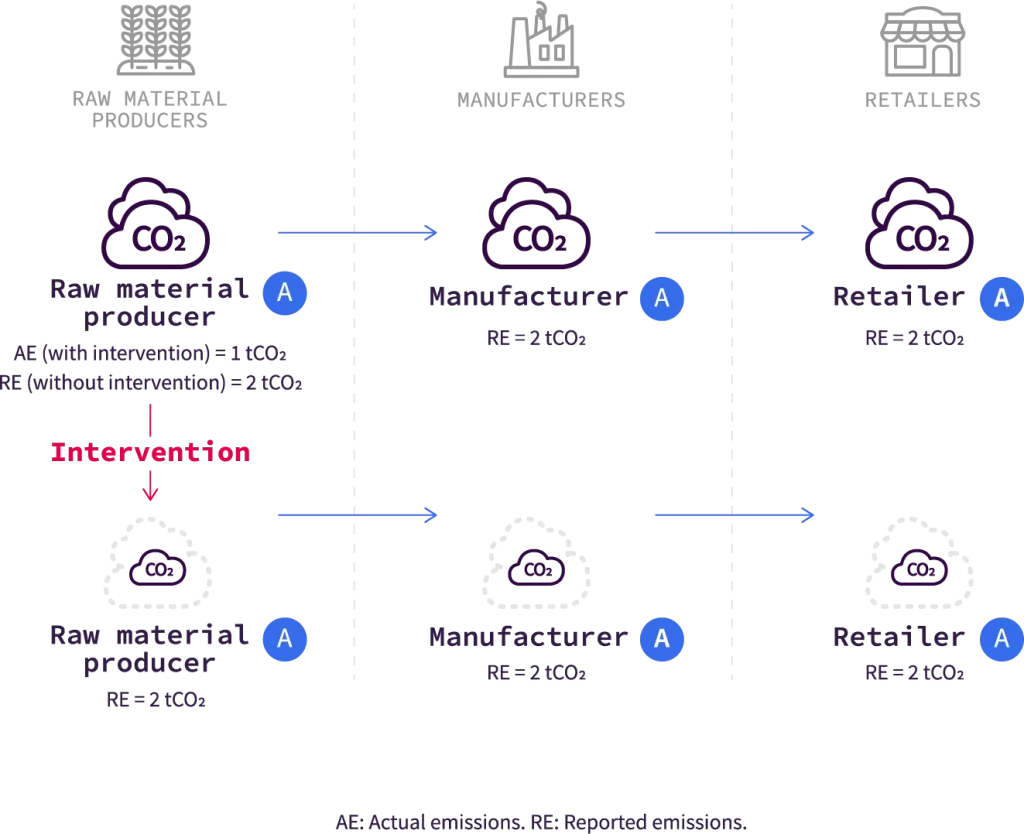

This principle doesn’t stop at inventory accounting; it also applies to the target level. If one company’s target is to reduce direct emissions from generating its product and another company has a target to reduce indirect emissions from buying that product, they will mutually benefit from one another’s reductions. For example, if a raw material producer reduces its emissions, both the manufacturer and the retailer will be able to claim that their scope 3 emissions have decreased if the raw material producer’s reduction is kept in that value chain.

This overlapping of targets presents an opportunity to foster collaboration across the value chain that will ultimately accelerate emissions reductions.

Double counting in this instance refers to the shared responsibility of companies and nations to reduce emissions. This situation could arise if a national government decides to promote green energies over coal for instance. Companies operating in this country would benefit from improved access to (or funding for) green energies and would be able to focus their emissions reductions efforts in countries where there is weaker (or a lack of) government climate action. In this case, both the government and the companies can account for the same reduction – one at the national level and the other in corporate inventories.

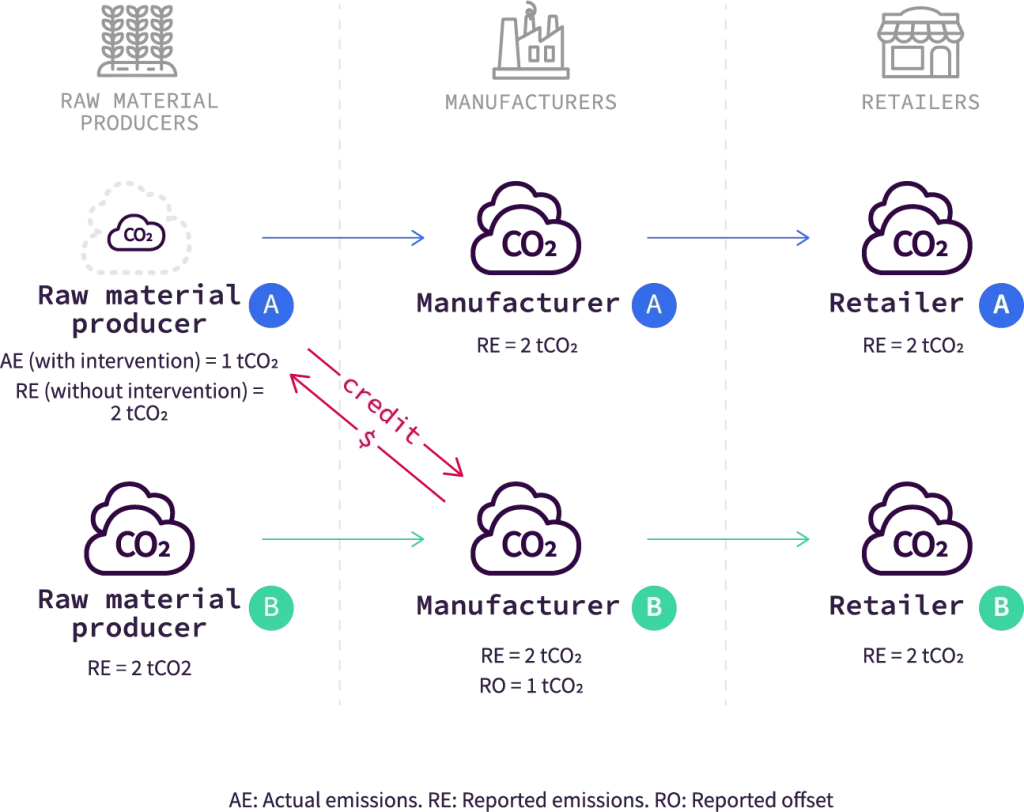

Emissions reductions or removals generated by any entity within a supply chain can be sold as carbon credits on the voluntary carbon market. When a company – or one of its raw material producers – sells such credits, it must ensure that these reductions or removals are not double-counted in its corporate inventory. To prevent this, the company is required to adjust its inventory to reflect the credits sold.

This adjustment is necessary because other companies purchase these credits with the intention of claiming them as unique emission reductions or removals. They use the credits to offset or compensate for their own emissions. If the seller does not adjust its inventory while the buyer uses the credit as an offset, the same reduction or removal is claimed twice – resulting in double counting.

Large multinational companies face an added risk because credits can be generated and sold by any entity within their value chain. This creates the possibility of unintentional and often hard-to-detect double counting in the multinational’s corporate inventory. To mitigate this risk, it is recommended that multinationals strengthen value chain traceability and create incentives for climate action to remain within the value chain. For example, they could offer a premium for emissions reductions achieved internally, ensuring that claims related to climate action stay inside the value chain rather than being transferred externally.

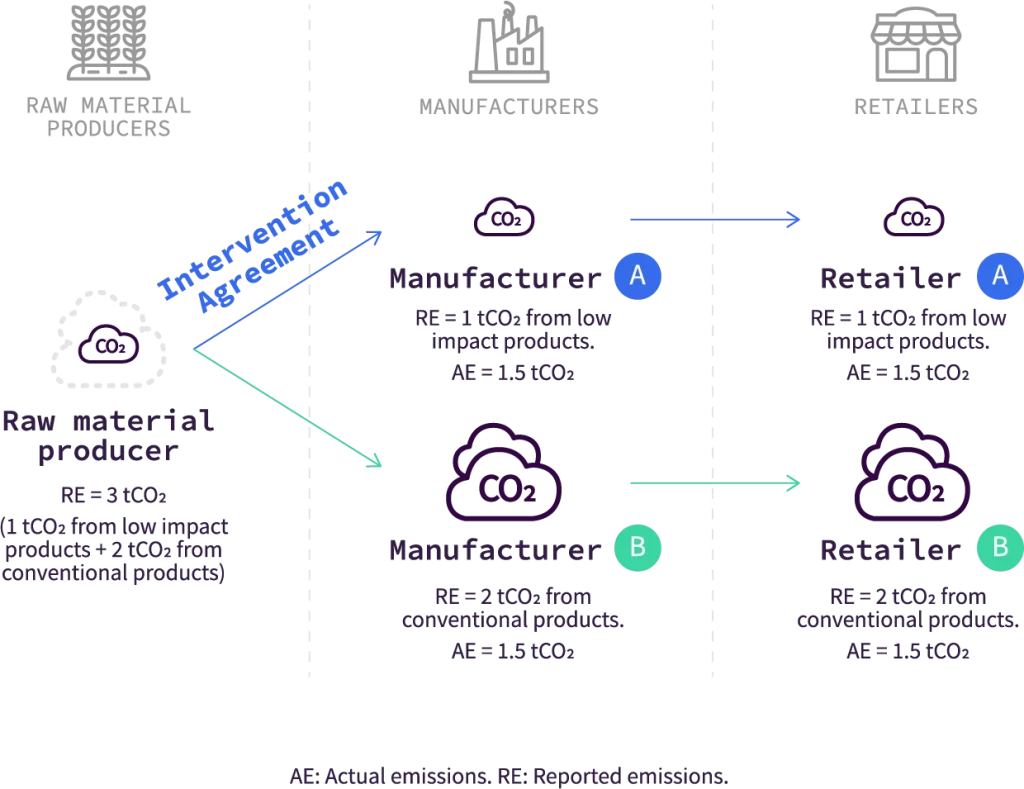

A raw material producer cannot allocate reduced emissions from a given amount of a “low-emission” product or service to more than one customer at a time. This is ensured through the chain of custody (CoC) requirements, which monitor and transfer these volumes. Let’s say a cocoa supplier has implemented an intervention in agreement with one of its customers, cocoa manufacturer A, for the volume of products they purchase. Cocoa manufacturer A is the only manufacturer that will be able to account for this reduction in its inventory, which can then be transferred to its own customer, retailer A. If both cocoa manufacturer A and retailer A can claim these reductions, they cannot be claimed by the cocoa supplier’s other customers, manufacturer B and retailer B, even if they also purchase cocoa from that supplier.

It is important to note, however, that not all intervention agreements are automatically valid. For a transfer of reductions to be credible, it must align with the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP) traceability requirements. In practice, this means reductions can only be transferred through recognized attribution methods that ensure integrity and avoid double counting.

To allocate the reduction to its customer after carrying out an intervention, the raw material producer must follow robust and transparent attribution rules. There are two ways to do this:

Or,

In both cases, we recommend following a contractual agreement and a proper accounting system at the raw material producer level to track the amount of improved raw materials over a specified timeframe to avoid double counting. To prevent a customer that isn’t authorized to claim a reduction from doing so, raw material producers should report emissions factors for improved and unimproved raw materials separately. Doing so allows companies that can’t claim the reduction, or can only claim a partial reduction, to use the appropriate emissions factor and avoid double counting improvements already claimed by an industry peer.

Collaborate on interventions, measuring and assigning reductions.

When partners in the same value chain work collectively to implement value chain interventions, everyone wins. Keeping the activity within the value chain, rather than selling carbon credits to external organizations, allows you to focus resources on reductions as well as help others in your value chain reach their targets. Raw material producers should establish emissions factors for improved and unimproved raw materials and report them separately to their customers to ensure that companies able to claim the reduction can capture the full benefits, and those unable to claim a reduction will use the correct emissions factors.

Don’t claim reductions without doing adequate due diligence to ensure that they’re not already being claimed by another similar actor or value chain.

For both credibility and progress tracking purposes, it’s critical to know where emissions reductions took place and whether an actor at a similar stage of the value chain might have already claimed them. If buyers know that certain credits are part of a scope 3 intervention and that another company is buying them as offsets, they shouldn’t claim them as reductions.

Develop a policy for shared accountability and double counting and communicate it with key stakeholders.

This policy should be communicated internally and must clearly set forth how to reconcile reductions related to other programs. It should also outline which types of double counting are (or are not) considered and why, and situations where double counting may arise, particularly in relation to scope 3 reductions, to limit the likelihood of misinterpretation, to build confidence for future claims and to increase transparency.

We have answers. Get in touch with our team today and let us guide you through the solutions that might help you on your journey toward a sustainable supply chain.

Charlotte Bande

Global Food + Beverage Lead

Géraldine Noé

Global Climate Strategy + Risk Lead

Marcial Vargas-Gonzalez

Global Science + Innovation Lead

Pierre Collet

Global Footprint Lead, France

01

This chapter covers when to rebaseline, how to implement a clear base-year recalculation policy, and best practices for communication.

Read

02

This chapter considers data management tools and best practices for using primary data to estimate the impact reduction potential of interventions and track progress in the supply chain.

Read

03

This chapter covers how chain of custody connects verified sustainability results to the goods moving through supply chains, ensuring reductions are credible, traceable and countable toward climate targets.

Read

04 – Currently reading

This chapter focuses on how to manage the double counting of emissions reductions when considering real progress toward a sustainable supply chain.

Read

05

This chapter focuses on how uncertainty shapes sustainability accounting, where it typically arises in scope 3 data, and what companies can do to manage it.

Read