01

This year, your footprint shows a decrease of a few points. But are your base-year emissions relevant enough to make this comparison?

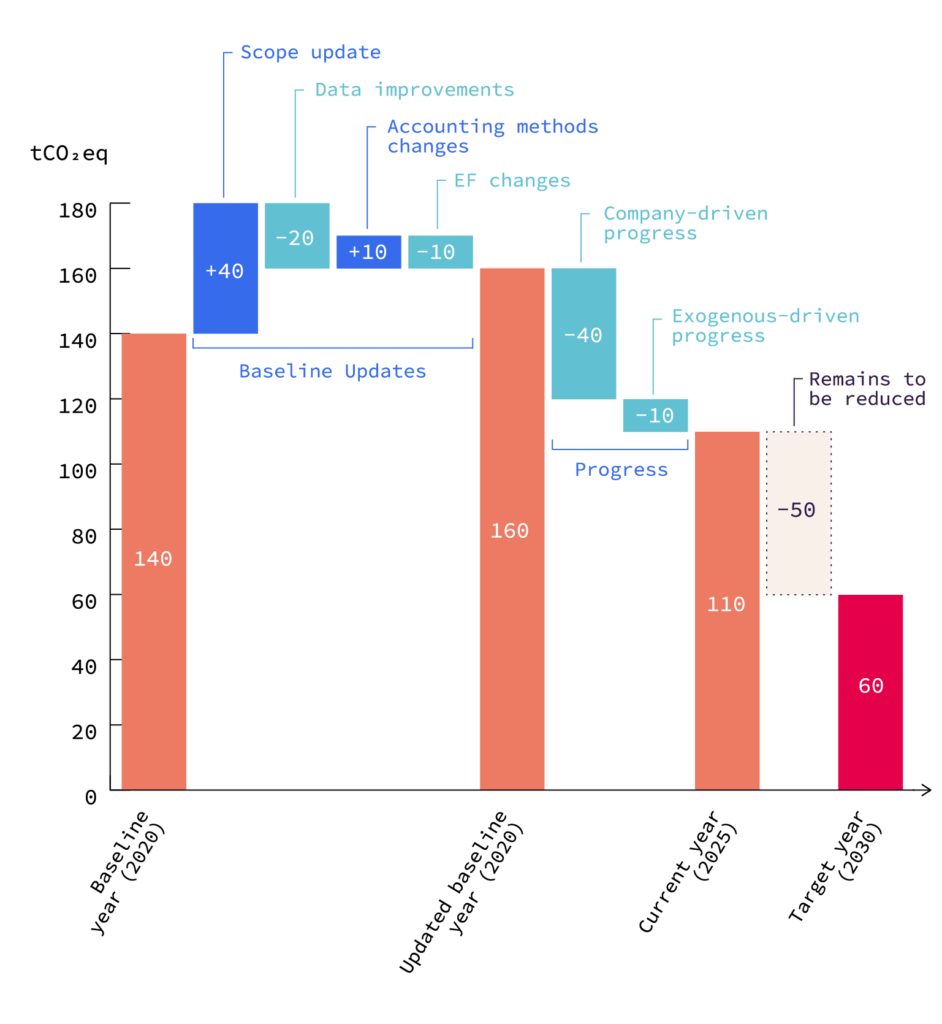

If your accounting methodology, scope or data has changed, it may be time to recalculate your base-year emissions to align them with your current reporting year. We call this rebaselining: a process undertaken by an organization to recalculate its base-year emissions to align them with its current reporting year. By measuring the difference between two footprints calculated using the same methodology, data granularity and scope, organizations will have the most complete and accurate picture of their true progress.

A robust and straightforward model makes rebaselining easier for organizations and helps integrate it into regular reporting practice. When done consistently – ideally every year – and paired with open communication with both internal teams and external stakeholders such as investors, NGOs and clients, it fosters transparency and trust.

In this chapter, we’ll take a look at when and how to rebaseline, and why it’s critical for tracking true progress, not just methodological or scope changes.

In the context of sustainability, progress can mean different things to different companies. At Quantis, we define progress as the actions that lead to real reductions or actions that aim to divest from polluting activities. Both will lead to actual reduction of a company’s emissions, determined by measuring the difference between two footprints that were calculated using the same methodology, data granularity and scope. That last part is key, and the very reason rebaselining is so critical to an accurate analysis of progress. Why? Let’s say your company decides to sell off an entity or start using different, more accurate emissions factors. Both decisions could lead to a decrease in your company’s carbon footprint compared to your base year, however neither qualifies as real progress – they’re simply shifts in scope or data quality. The only way to get a true sense of your progress is to be consistent in your approach to measuring your base-year and your current-year footprints.

It’s also worth noting the kind of progress being made. Progress can be categorized in two ways – company driven or linked to exogeneous factors – as determined by whether it’s triggered by company-related or external drivers. Company-related drivers are company-initiated actions to decrease emissions, such as altering the type or reducing the quantity of materials used in key products. Exogeneous drivers are actions taken by others – sectors, countries or peers – that indirectly benefit a company, such as a region improving its energy mix with renewables.

Ideally, an organization should rebaseline on a regular basis to ensure good traceability of changes. Many companies already build rebaselining into their annual reporting cycle, making it a regular part of tracking progress. Rebaselining should be done when relevant and strategic and at a minimum when there is a significant change in its structure or inventory. This threshold for significance is defined by the Science-Based Target initiative (SBTi) as 5% or less in an organization’s total base-year emissions. Note that this 5% is a relative value (between scopes) rather than an absolute one as targets are set by scope.

In the case of subsidiaries, rebaselining is a good option if that company reached the 5% shift threshold of its own inventory while working on its own reduction strategy, independent of the parent corporation.

Example

In 2021, Company X established its science-based target baseline using secondary spend-based data for purchased goods. At the time, emissions were estimated at 500,000 t CO₂-eq. Two years later, the company launched a supplier engagement program to improve data accuracy, and several key suppliers provided primary activity data. When recalculating with this new primary data, Company X found that its 2021 emissions were closer to 420,000 t CO₂-eq. Since the difference exceeded SBTi’s 5% materiality threshold, the company is required to recalculate its baseline emissions. The updated 2021 baseline is therefore reset to 420,000 tCO₂e, and the original reduction ambition of 30% by 2030 was reapplied. This meant the 2030 target shifted from 350,000 tCO₂e (based on secondary data) to 294,000 tCO₂e (based on primary data).

By transparently documenting the process, recalculating the updated targets and verifying their validity against SBTi requirements (and potentially resubmitting to SBTi them if needed), Company X not only complied with SBTi criteria but also strengthened stakeholder confidence through higher-quality, supplier-reported data.

Below, we’ve outlined some of the activities that could trigger the need for rebaselining. It’s important to remember that the changes in emissions resulting from these activities should not be claimed as reductions, as they are the result of a footprint shift rather than an actual effort.

Scope updates

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As), divestments, outsourcing or insourcing, changes in ownership, control or business activities are changes in scope that necessitate rebaselining. In the specific case of M&As, if your company has recently acquired or merged with another entity, rebaselining should only take place when full integration has occurred. On the other hand, organic growth (no matter how big) or decline, does not trigger rebaselining.

Bear in mind that changes in ownership could shift activities between scopes if your company is already reporting accurately on the three scopes. Such shifts would create the need for rebaselining each scope, even if this doesn’t impact your total scope 1,2 & 3 emissions.

Including emissions previously excluded from the boundary also falls into this category, such as emissions stemming from e-commerce activities which weren’t included in an initial footprint.

Activity data improvements

A significant change in the quality of company data can lead to higher or lower reported emissions, even if no real changes in practices occurred. For example, you might replace spend-based estimates with supplier-provided primary data, adopt a system that captures more granular categories, or correct previously identified errors. Rebaselining ensures that these improvements in data quality are reflected clearly, without overstating or understating progress.

Sometimes, company data updates capture both methodological refinements and real performance shifts. For instance, supplier data might show more accurate emission factors and reduced energy use. In such cases, it’s important to scope carefully: if you have the resources, reconstruct the baseline to isolate real progress. If not, the conservative approach is to treat these updates as methodological changes – with the exception of electricity mix improvements, which reflect genuine external reductions.

Changes to accounting methods

Making changes to the methodologies used to align with new standards or better knowledge could impact your emissions, necessitating rebaselining. For example, adjusting the way land use change is accounted for in a model following the release of the GHG Protocol Land Sector and Removals Guidance could lead to an increase or decrease of emissions, related only to the accounting rules change. As a methodological change, this requires rebaselining before any assessment of whether progress has been made.

Changes in emissions factors

Rebaselining is necessary when an organization starts using an emissions factor that is more robust, from a different database, or more representative of its activities. It’s important to distinguish between updates to emissions factors from the same database, which may reflect genuine improvements such as a cleaner electricity mix, and those from different databases, which usually represent methodological changes. While the former does count as progress, the latter should not. Because database updates often mix both, scoping carefully helps avoid overstating reductions. If resources are limited, remember that it’s often more credible to treat these as methodological changes only.

Do you need to rebaseline? The decision tree below can help you determine the answer.

You’ve determined that you need to rebaseline. The only question that remains is how to get started.

In concrete terms, rebaselining entails plugging base-year data into an updated model that reflects structural or methodological changes — such as acquisitions, divestments, scope adjustments, or updated calculation methods. The latter can include revised emission factors, improved activity data, or changes in accounting approaches — all of which impact the baseline. The goal is to ensure the baseline remains accurate and aligned with your current emissions profile.

To illustrate how this works, let’s look at an example. An organization has acquired a new entity that represents more than 5% of its revenue or is a significant impact driver. Rebaselining would require the following process:

This process allows for the measurement of a company’s actual impact by comparing two identical models and showcasing the progress made towards overall goals. When undertaking this exercise, you can either approach it high-level, focusing solely on progress vs. change, or you can do a deep dive and track the various company-related drivers or exogeneous drivers of progress.

One question that often arises is whether emission factor (EF) updates, particularly from databases, should count as progress. The short answer: in most cases, they should not. Database updates are generally considered methodological changes rather than real reductions, because they reflect refinements in how impacts are modeled rather than actual shifts in company performance. The notable exception is when EF updates capture genuine external progress, such as a cleaner electricity mix in a given region.

The guiding principle is to always distinguish between real progress (company-driven actions or exogenous improvements) and methodological updates (like EF changes). In practice, the two are often entangled – for example, when switching from generic to primary supplier data, or when a database revision incorporates both improved methods and external market shifts. In these “difficult cases,” companies need to scope carefully: if budget and resources allow, back-casting the baseline can help isolate real progress; if not, the conservative approach is to treat the update as methodological change only.

The final results will look as follows:

The SBTi expects baselines and targets to evolve over time due to changes in business activities or methodological updates. To ensure continued alignment, companies must assess whether these changes – such as aforementioned acquisitions, divestments, or revised calculation methods – trigger a significant shift in GHG inventory, typically defined as a ≥5% change in base year emissions. When this threshold is met, companies are required to follow a defined recalculation process, which may include updating their base year, reassessing targets for validity, and, if necessary, resubmitting for revalidation under the latest SBTi criteria. The process is outlined here in the SBTi FAQ.

Depending on the method originally used to set your target(s), rebaselining may lead to a notable change in your existing approved targets. While the SBTi expects companies to recalculate and verify whether their targets remain valid following a rebaselining – in particular that their ambition and coverage remain aligned with SBTi criteria – you do not need to inform the SBTi of the exercise unless it affects your approved targets. If the results of the target recalculation show that your targets no longer meet one or more SBTi criteria, a target revalidation requirement is triggered, and you must formally resubmit the updated targets for validation.

The following paragraphs highlight how targets might be affected according to the target setting method chosen

Absolute reduction targets

For targets set using the absolute contraction approach, the target will generally not change. The ambition of the target – defined as the percentage reduction at target year from the base year emissions – will not change, only the absolute value of the reduction in GHG emissions.

For example, if your absolute target was set at 20%, representing a 24 tCO2-eq reduction from your 120 tCO2-eq baseline, the target will remain 20% following rebaselining, but with an updated baseline of 150 tCO2-eq. The actual reduction will now be 30 tCO2-eq.

Corporate targets that are set as the consolidation of various business units may require updating if the business units’ relative importance changes as a result of the rebaselining.

Point of attention: If coverage of your approved targets is less than 100%, you must verify that the coverage still meets SBTi criteria when applied to the updated base year inventory (e.g., >67% of scope 3 emissions in the near term, >90% for scope 1 and 2).

Sectoral approach targets

For targets set using the Sectoral Decarbonization Approach (SDA), such as cement or the commodity pathways of FLAG, should, however, be revised after rebaselining because the base-year intensity measure will likely change. Targets should be revised after rebaselining, as the base-year intensity measure will likely change.

Taking a simplified example for Cement (SDA): If your baseline intensity was 0.50 tCO₂e/tonne cement and the SDA pathway requires 0.40 tCO₂e/tonne by 2030, a rebaselining that revises the 2019 baseline to 0.56 means the 2030 pathway target (0.40 tCO₂e/tonne) stays the same, but the required reduction deepens from 0.10 to 0.16 tCO₂e/tonne (i.e. from –20% to –28.6%).

The target values and any absolute emissions projections should then be adapted accordingly.

Point of attention: Companies must confirm that recalculated targets still comply with SBTi criteria, in particular ambition and coverage thresholds

Regardless of the approach used to set your targets, it’s crucial to review your roadmap after rebaselining to ensure it will still get you to your targets. Over or underestimating certain GHG Protocol reporting categories could lead to a change in the reduction potential of key actions.

Manage stakeholders’ expectations on rebaselining

Be upfront and transparent with executives, higher-level management and external stakeholders from the beginning, and flag that baselines can change in a significant way. A robust baseline can take two to three years to develop, and will evolve alongside changes in standards, methodologies and data precision. Carbon accounting is very different from financial accounting: it is neither perfect nor static. The following are challenges and necessary considerations that should be communicated clearly and frequently to senior leaders:

Implement a clear base-year recalculation policy.

In this policy, you should aim to address any questions around when, why and how you will rebaseline. Having clear guidelines in place concerning what internal and external circumstances trigger rebaselining will facilitate decision-making and allow consideration for the most pragmatic route for your company to take. The objective of the policy should be to enhance clarity around progress tracking processes.

Rebaseline when change is significant, when you need to be compliant or to track progress more accurately.

The SBTi defines significant change as a minimum of 5% of the total corporate footprint. If major corporate activities are underway, it could be time to rebaseline. When you do rebaseline, remember to check the impact on targets and roadmaps, and determine if they are still relevant and accurate. If you’re not sure how to determine this, you can check-out the decision tree above.

Rebaseline annually, and consolidate minor changes into a single baseline update.

Plan to update your baseline whenever relevant – ideally annually, as part of your annual reporting cycle. This helps keep your inventories consistent and makes year-on-year progress clear. If only very small changes occur – for example, less than 5% of the total corporate footprint (that is, they don’t hit the “significant” threshold set by the SBTi) – you can group changes and limit yearly small movements. When you do rebaseline, review other changes that could impact your footprint to ensure they will not need to be updated in the near future.

Use accurate and qualitative communication around rebaselining.

To promote transparency and gain trust, it’s important to communicate the reasons behind any fluctuations, such as a change in methodology, scope or real emissions reduction progress, to both internal and external stakeholders. Best practice is to explain the origin and type of changes and identify where in the inventory these adjustments are applied. Companies may choose to provide either a simple disclosure of the new baseline or a more detailed explanation of the recalculation process.

We have answers. Get in touch with our team today and let us guide you through the solutions that might help you on your journey toward a sustainable supply chain.

Charlotte Bande

Global Food + Beverage Lead

Pierre Collet

Global Footprint Lead, France

Géraldine Noé

Global Climate Strategy + Risk Lead

Marcial Vargas-Gonzalez

Global Science + Innovation Lead

01 – Currently reading

This chapter covers when to rebaseline, how to implement a clear base-year recalculation policy, and best practices for communication.

Read

02

This chapter considers data management tools and best practices for using primary data to estimate the impact reduction potential of interventions and track progress in the supply chain.

Read

03

This chapter covers how chain of custody connects verified sustainability results to the goods moving through supply chains, ensuring reductions are credible, traceable and countable toward climate targets.

Read

04

This chapter focuses on how to manage the double counting of emissions reductions when considering real progress toward a sustainable supply chain.

Read

05

This chapter focuses on how uncertainty shapes sustainability accounting, where it typically arises in scope 3 data, and what companies can do to manage it.

Read

You have 50% of the chapter left to read. Please share your email to continue the reading.

By submitting, you consent to allow Quantis to share sustainability-related content.

You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information, please review our Privacy Policy.

I’d rather not. Please take me home.