03

Credible claims depend on more than action. They require systems that connect verified results to the volumes moving through supply chains.

Sustainability claims are everywhere today – on products, in corporate reports, across supply chains. But behind the labels and numbers, the rules for how impacts are tracked and transferred are still evolving. Some approaches are rigorous, others less so, and the result is a landscape that can be hard to navigate.

This matters because the credibility of a claim doesn’t rest only on the actions taken to reduce emissions or environmental impacts. In practice, those actions – known as value chain interventions – introduce changes in technologies, practices or sourcing that generate measurable outcomes. The challenge is ensuring those outcomes are measured, allocated and connected to the goods and services moving through the value chain. Without clear transfer systems, even genuine results risk being questioned or lost in translation.

This is where chain of custody (CoC) comes in. CoC doesn’t create the impact data, but it safeguards their transfer, so that benefits remain intact and defensible all along the chain. The GHG Protocol, in its forthcoming Land Sector and Removals Guidance, will further clarify expectations for demonstrating physical traceability via a Chain of Custody. To understand how CoC works – and why it’s critical for credible supply chain claims – we first need to define what it is and the different models it can take.

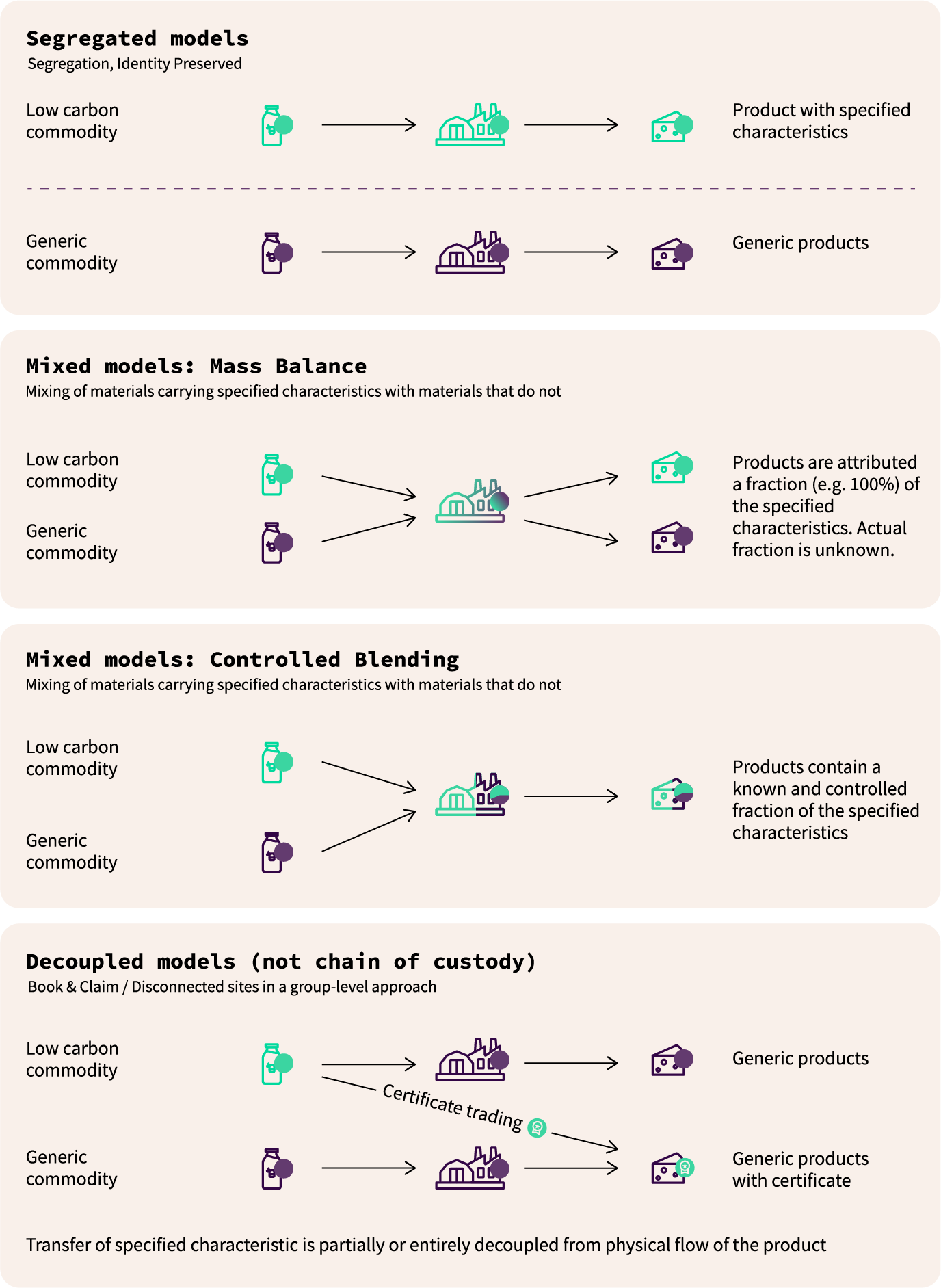

Chain of custody (CoC) is a structured system that governs how materials and their defining specified characteristics such as origin, certification or environmental profile are transferred and verified as they move between organizations. It answers a simple question: How are volumes and their characteristics passed along the chain, and under what controls?

CoC focuses on preserving specified characteristics. These are the material, product or production characteristics the system is designed to keep intact as goods are traded and transformed.

Different CoC models set the rules for how materials should be treated, including how specific claims such as “certified” or “low carbon” are assigned, traced and maintained even when materials are mixed or transformed during production. These systems help to:

To navigate this complexity, companies don’t have to start from scratch. A number of established initiatives are already providing common definitions and practical guidance on how chain of custody should work in sustainability systems. These standards serve as reference points for designing credible approaches, and for ensuring that claims linked to value chain interventions are both consistent and verifiable.

Chain of custody, traditionally used to underpin claims such “organic” or “vegan”, is now becoming relevant in greenhouse gas accounting. The GHG Protocol has long set the baseline for corporate emissions reporting, and its forthcoming Land Sector and Removals Guidance will further tighten expectations for demonstrating physical traceability via a Chain of custody. Building on that foundation, the SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard is pushing companies to show a clear physical link between verified outcomes and the goods they buy.

What this means in practice is that reductions, removals and avoided impacts generated in value chains only count as Scope 3 progress if they can be physically linked to the volumes companies actually source. We will refer to this as in-value chain reporting.

If demonstrated physical traceability is not yet achievable, companies can use market-based approaches, which can mobilize finance and signal demand but generally sit outside the inventory, and thus treated as “indirect mitigation” rather than direct progress towards targets.

In summary, as standards evolve, chain of custody is becoming the mechanism that determines whether intervention outcomes can flow into scope 3 reporting and toward climate targets – or risk being sidelined.

Not all chain of custody models do the same job. If you want to report value chain interventions as progress, you need a model that keeps a clear connection between the inputs that carry specified characteristics and the outputs that receive them.

These models keep qualifying material separate from non-qualifying material from input to output. Because these models maintain a direct physical link, they support in-value chain reporting, outcomes stay attached to sourced volumes and can be counted toward scope 3 targets.

Example: A coffee roaster sourcing beans from multiple certified farms can mix those beans together, but none from non-certified farms. The roaster can credibly claim the final blend is 100% certified.

These allow mixing or substitution of qualifying and non-qualifying material under defined rules. In particular, some types of Mass Balance (‘MB’) CoC models guarantee the possibility of physical presence of material carrying Specified Characteristic via a process that reconciles input and output volumes.

Example: An aluminum producer purchases both low-carbon and conventional aluminum inputs. Within a quarterly balancing period, the producer ensures that no more low-carbon claims are issued than the verified low-carbon input received, even if outputs are mixed.

The MB system can be defined on different geographic (batch, site or multi-site levels) or temporal boundaries. When guardrails are tight and documented, some MB CoC maintain a documented link between inputs and outputs, and can thus support in-value chain reporting. But if boundaries are too loose or guardrails weak, the risk of misallocation rises – and results may need to be reported instead through market-based approaches.

What a credible MB CoC must have for in-value chain reporting

Design the system using ISEAL’s three levers – transfer boundaries, temporal restrictions and product groups – and apply volume reconciliation so outputs with specified characteristics never exceed eligible inputs, after conversion factors and loss. Inconsistent application undermines integrity and can break physical traceability.

Rules are tightening. ISEAL has refined model definitions, some sectors are shaping practical mass balance guardrails, and GHG accounting guidance is advancing. Build for tightening boundaries, shorter periods and stricter stock rules over time.

Mass balance works best when it mirrors how the material actually moves. Set clear rules and records that keep the link between inputs and outputs, so verified results can flow into scope 3 with confidence.

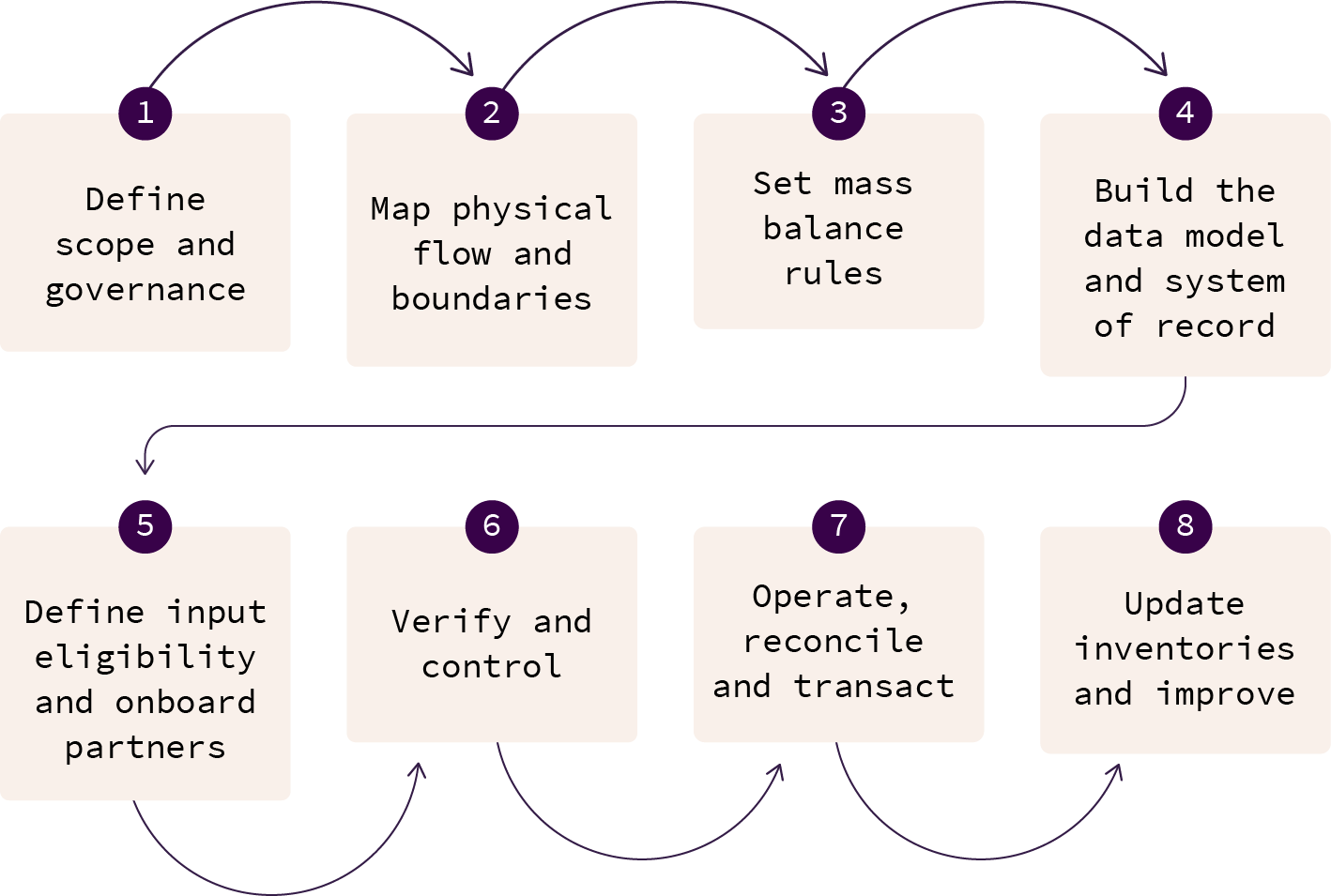

1. Define scope and governance

Decide what claim you want to make – whether product-linked, inventory-linked or indirect/market-based – and confirm mass balance as the model if relevant. Define the products, sites and time window you will cover. Assign clear decision rights across procurement, operations, sustainability, legal and IT. Draft the exact claim language now so design choices support it.

2. Map physical flows and boundaries

Draw how inputs move through storage and processing to become outputs. Mark loss points, co products and transfer nodes. Choose the smallest practical boundary that reflects real logistics and can be audited. For multi-site designs, show the operational link that justifies grouping.

3. Set mass balance rules

Select batch, site or multi-site. Pick a balancing period that fits material movement, often monthly or quarterly at the start. Define conversion yields, loss factors and stock rules in writing. State that no output can carry more specified characteristics than eligible inputs for the period.

4. Build the data model and system of record

List the data fields needed at each handoff. Typical fields include lot ID, date, site, input and output volumes, specified characteristic amounts and any expiry. Stand up a controlled ledger for pilots and link to ERP or a registry as you mature. Every transfer must leave an auditable trail.

5. Define input eligibility and onboard partners

Set the criteria that make an input qualifying, including intervention evidence and verification status. Explain the data you will collect and the checks you will run. Add participation duties, data sharing and verification rights to contracts. Pilot with a few partners before scaling.

6. Verify and control

Plan independent checks of input eligibility, data integrity, reconciliation and allocation logic. Agree sampling methods and the evidence list. Add internal controls such as monthly reconciliations, management sign off and pre-publication claim reviews. Record findings and close them out.

7. Operate, reconcile and transact

Capture data at each transfer and reconcile on your chosen cadence. Lock the ledger at period end and carry forward only eligible stock per your rules. Issue transfer documents that show specified characteristic amounts, sites covered, the balancing period and any expiry. Buyers record the same.

8. Update inventories and improve

Turn verified outcomes into updated emission factors where allowed and carry them into Scope 3 accounting. Track simple indicators like data completeness, reconciliation accuracy, audit findings and partner participation. Tighten boundaries and shorten balancing periods as data quality improves. Expand only where physical connectivity and auditability can be maintained.

If you plan to set up a CoC to track progress or to enable customers to claim reductions, first get familiar with the main challenges and how to avoid them.

To implement chain of custody with integrity and carry results into scope 3 with confidence, consider the following recommendations.

Choose the right CoC for each commodity.

Match the model to how the material actually moves. Where physical traceability is possible, use identity preserved, segregation, or a well-guarded mass balance. If traceability is limited, plan a path to it.

Engage stakeholders early.

Align farmers, processors, traders and logistics on data, verification and claims. Put participation and data sharing into contracts.

If you run the project, build the CoC with it.

Co-design the rules with value chain actors from the start. Define eligibility, data fields and balancing rules, then pilot and scale. Keep transfer records that support inventory updates.

Track progress with eligible models.

To include results in scope 3 emission factors and align with the GHG Protocol, use at least a mass balance CoC with independent verification, clear allocation, and safeguards against double counting. If not, treat it as indirect mitigation and disclose it accordingly.

Use market-based tools as a bridge.

When a fully GHGP-compliant chain of custody isn’t yet feasible – especially in immature, fragmented or global supply chains – book and claim can play a role in mobilizing finance and signaling demand. Disclose these transactions as indirect mitigation in line with evolving SBTi Net Zero guidance and use them as a stepping stone while you build the traceability and partnerships needed for value chain accounting.

Book + claim:

We have answers. Get in touch with our team today and let us guide you through the solutions that might help you on your journey toward a sustainable supply chain.

Alaïs Faucon

Sustainability Manager, Food + Beverage

Jean-André Bonnardel

Global Supply Chain Lead

Matt Foerster

Global Land + Agriculture Lead

Marcial Vargas-Gonzalez

Global Science + Innovation Lead

01

This chapter covers when to rebaseline, how to implement a clear base-year recalculation policy, and best practices for communication.

Read

02

This chapter considers data management tools and best practices for using primary data to estimate the impact reduction potential of interventions and track progress in the supply chain.

Read

03 – Currently reading

This chapter covers how chain of custody connects verified sustainability results to the goods moving through supply chains, ensuring reductions are credible, traceable and countable toward climate targets.

Read

04

This chapter focuses on how to manage the double counting of emissions reductions when considering real progress toward a sustainable supply chain.

Read

05

This chapter focuses on how uncertainty shapes sustainability accounting, where it typically arises in scope 3 data, and what companies can do to manage it.

Read

Several guidance documents and standards provide the foundation for credible chain of custody (CoC) design in greenhouse gas accounting and sustainability claims. Here are a few to keep in mind when talking about CoC:

ISEAL Chain of Custody Models and Definitions (2025). Offers a common reference language and clear definitions of CoC models, including identity preservation, segregation, controlled blending, mass balance and book and claim. It also sets out conditions for when each model is appropriate, and how to maintain integrity through boundaries, reconciliation and verification.

Value Change Initiative (VCI) Guidance. While not yet available, an updated guidance is currently being drafted by VCI.

GHG Protocol Land Sector and Removals Guidance (LSRG). Establishes accounting requirements for land use emissions and removals, including traceability expectations that will apply across value chains.

Something to keep in mind: The landscape is rapidly evolving. We will continue to monitor developments and update our guidance to reflect the latest changes.

You have 50% of the chapter left to read. Please share your email to continue the reading.

By submitting, you consent to allow Quantis to share sustainability-related content.

You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information, please review our Privacy Policy.

I’d rather not. Please take me home.